News

It’s all downhill from here for British growth

In a rare instance of good news for Rachel Reeves, the UK economy grew by 0.7 pc between January and March, ahead of forecasts of 0.6 pc.

The latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) also revealed that GDP per head – a rough measure of living standards – climbed by 0.5pc in the first three months of the year.

In response to the figures, the Chancellor said: “Up against a backdrop of global uncertainty we are making the right choices now in the national interest.”

However, the numbers mask a challenging outlook for Reeves. The GDP rise, which marked the strongest quarter in a year, came as companies scrambled to ship goods across the Atlantic before Donald Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs announcement on April 2.

Economists do not expect that momentum to continue, and forecasts for the year ahead paint a grim picture for the British economy as the impact of higher taxes and tariffs kick in.

“The main reason that GDP was stronger than everyone expected appears to be because US and UK tax changes meant that more activity was pulled forward into the first quarter from the second,” says Paul Dales, the chief UK economist at Capital Economics.

“This means the second quarter may well be weaker than widely expected and the best part of the year may already be behind us.”

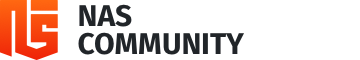

The Bank of England made this point abundantly clear during its latest assessment of the economy last week. According to the rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), the growth in the first quarter was down largely to “erratic factors” rather than an underlying strength in the economy.

In fact, Threadneedle Street estimated that underlying growth was around zero at the start of the year, highlighting the inherent weakness of the economy.

In particular, the MPC warned that Trump’s trade war meant growth was likely to “slow sharply” in the second quarter of the year to a dreary 0.1 pc.

While the president has backed away from the worst of his tariff policies after striking a trade deal with the UK and rolling back levies on China, uncertainty abounds.

And tariffs are still a headache for British exporters. As it currently stands, the best UK exporters can hope for is 10pc baseline tariffs on goods sent to the US.

The additional cost of these levies has already forced many businesses to cut back on trade with the US or seek out different markets altogether.

“Despite last week’s trade agreement with the US, tariffs on UK exports to the US remain significantly higher than what they were prior to April,” says Yael Selfin, the chief economist at KPMG UK.

“Additionally, the indirect impact of trade tensions between the US and the EU will further constrain demand for UK exports.”

Worse still, countries looking to avoid Trump’s tariffs such as Chinese exporters may seek to dump cheap goods in the UK, undercutting the price of domestic producers and weighing further on their balance sheet.

It is not simply Trump’s trade policy that is hanging over Britain’s economy either: Reeves’s tax raid is likely to weigh on activity for the rest of the year.

In particular, economists are most concerned about the impact of the £25bn National Insurance tax increase, which came into force on April 1.

Businesses across a wide range of industries have been battling to cut costs in response to the tax raid, which has led to reduced hiring and higher job losses.

Earlier this week, figures from the ONS revealed that the number of jobs advertised fell to an average of 761,000 in the three months to April , down from 804,000 in the quarter prior.

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate rose to its highest rate in nearly four years.

Tina McKenzie, the policy chairman of the Federation of Small Businesses, says: “With official figures this week estimating the number of pay-rolled employees down more than 100,000 over the last year, there are clear signs that the increased costs and risks of giving someone a job are having an impact – threatening to snuff out these first flickers of growth.”

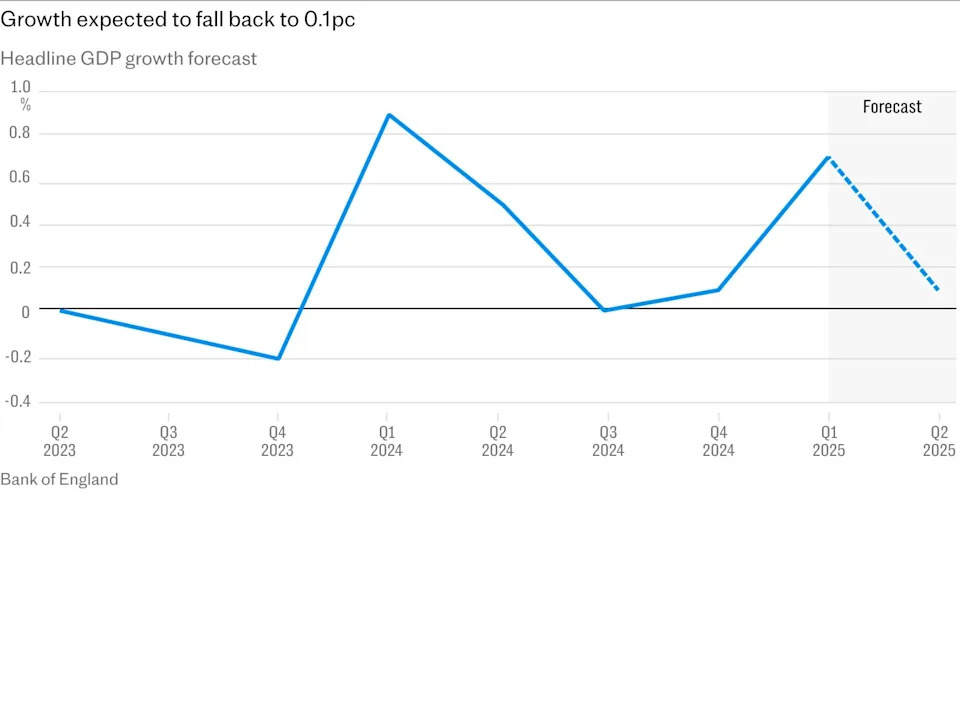

Adding to the economic storm clouds is inflation. The most recent figures from the ONS showed that inflation has slowed to 2.6pc in March, down from 2.8pc in February.

However, forecasts from the Bank of England reveal that it is likely to tick up to 3.5pc in the third quarter of 2025.

An expected rise in energy prices will fuel the rebound in price rises. Consumers and businesses will be alert for any change in costs, with many already prepared to cut back in response to higher prices.

“Momentum is likely to soften appreciably in the second quarter as the April rise in employer National Insurance and household energy prices hampers domestic demand, while rising global trade uncertainty impairs activity in trade-oriented industries,” says Kallum Pickering, the chief economist at Peel Hunt.

All of this means that the Chancellor’s celebrations over the first quarter GDP numbers are likely to be short-lived. The best is most likely already behind her.

Speaking after the GDP figures were released, Reeves said: “There’s clearly economic headwinds, and the world is changing. We can see that all around us, but we are a strong economy.”

The Chancellor underlined the importance of last week’s trade agreements with the US and India, adding that the Government was “working through the detail” on the US deal.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.